Just five miles to the north of Liverpool, England, a mid-summer auto race was about to begin. The tight, flat Aintree circuit wasn’t a showpiece of the motorsport world, and with the industrial surroundings it wasn’t especially picturesque. But by the end of this particular day in mid-July 1957, it would be remembered among auto racing’s greatest sites. On this course, a likely hero took a chance behind the wheel of a seeming unlikely car to break a decades-old losing streak.

Just five miles to the north of Liverpool, England, a mid-summer auto race was about to begin. The tight, flat Aintree circuit wasn’t a showpiece of the motorsport world, and with the industrial surroundings it wasn’t especially picturesque. But by the end of this particular day in mid-July 1957, it would be remembered among auto racing’s greatest sites. On this course, a likely hero took a chance behind the wheel of a seeming unlikely car to break a decades-old losing streak.

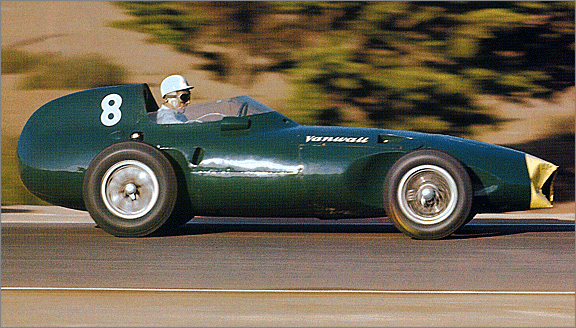

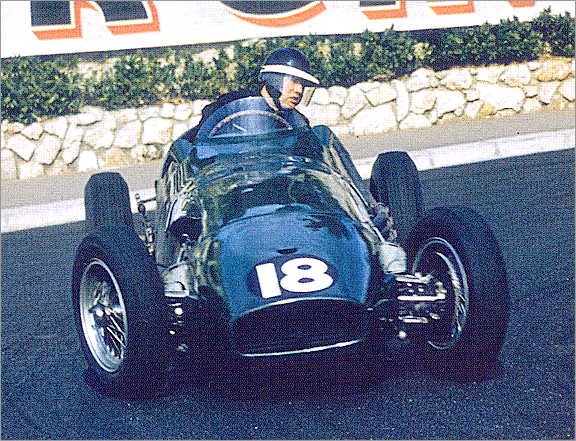

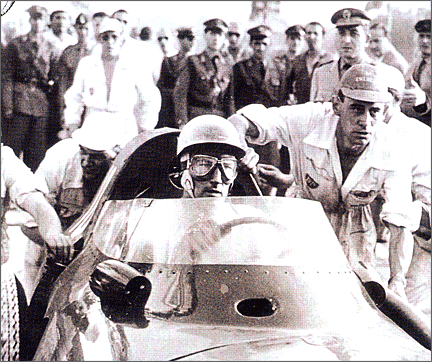

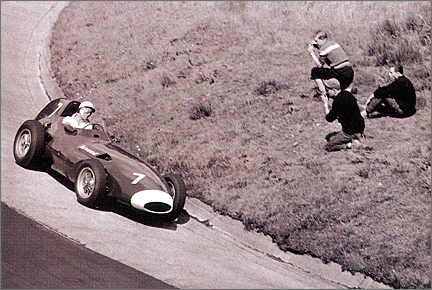

Amid the line of open-wheel machines waiting silently in front of the grandstands sat a driver in a deep-green car, Stirling Moss, a national treasure to the Britons that filled the stands. Unlike most of his contemporaries, he actually liked racing at Aintree, and tended to do well there. Two years earlier, he had driven this track in a Mercedes-Benz W196. Full of sophisticated engineering, that car had dominated the event and powered him to victory.

But today Moss would be doing battle in one of the most important races, the British Grand Prix, driving a machine created without the limitless resources of a major automaker like Mercedes. Rather, the man who conceived this car had never even built a car until a few years earlier. What’s more, it was born of an odd paradox of philosophies and components, employing on one hand some of the most sophisticated aerodynamics that had ever appeared on a racetrack, and on the other hand powered by an engine design hastily derived from motorcycle and military power-unit components.

And if this machine’s quirky composition wasn’t enough to limit his chances, Moss had history itself stacked against him. Grand Prix racing had for its 51-year history thus far been ruled almost entirely by Germans and Italians—emphasis on the Italians. Yes, there had been valiant attempts by Britons along the way.

And if this machine’s quirky composition wasn’t enough to limit his chances, Moss had history itself stacked against him. Grand Prix racing had for its 51-year history thus far been ruled almost entirely by Germans and Italians—emphasis on the Italians. Yes, there had been valiant attempts by Britons along the way.

But the sad truth was that an English car hadn’t won a championship Grand Prix since Henry Segrave drove a Sunbeam to victory at San Sebastian in 1924.

This could be a long day.

Watching from the pits was a heavyset, generally dour man in a gray sport coat, the car’s builder, Guy Anthony “Tony” Vandervell. He was one of Britain’s more powerful industrialists, a tireless worker who had been raised in the considerable wealth of his father’s CAV automotive-electrical-parts empire, then brashly made his own fortune on top of it. That second-generation success came by obtaining the European license to manufacture and sell the revolutionary new press-in engine bearings that did away with the time-consuming babbiting process. By the late 1930s, Vandervell practically had a lock on the market in Europe.

Vandervell had long been a racing fan; as a teenager he drove motorcycles and cars to victories in hill-climbs and even some wins at Brooklands. With such passion for motorsports, it was no surprise in 1945 that he enthusiastically signed on to driver Raymond Mays’ ambitious plan to build a successful all-British Grand Prix car.

Vandervell had long been a racing fan; as a teenager he drove motorcycles and cars to victories in hill-climbs and even some wins at Brooklands. With such passion for motorsports, it was no surprise in 1945 that he enthusiastically signed on to driver Raymond Mays’ ambitious plan to build a successful all-British Grand Prix car.

It was a tantalizing idea. Like Mays, Vandervell had for years watched with disdain as Italian and German teams ran away with race after race with hardly a British car in sight. Vandervell was ready to do something about it, and Mays’ fresh new consortium, succinctly titled British Racing Motors, could provide the perfect means.

Alas, despite BRM’s potential, its plodding bureaucracy moved too slowly for Vandervell’s taste. Months turned into years with little to show. Although he wouldn’t officially leave BRM until 1950, as early as 1947 he had already begun to entertain ideas of building his own team instead.

It would be from this quiet divergence that Vandervell would finally bring Britain to the pinnacle of international motor racing.

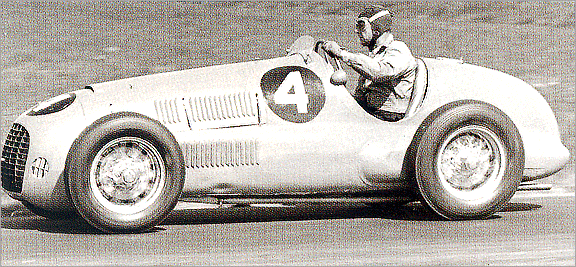

Vandervell knew he couldn’t jump out of BRM and immediately launch into building his own car. He needed to first learn more about Grand Prix racing and its technologies. To that end, he bought a series of Ferraris, had them painted green, and campaigned them under the name “Thin Wall Special,” after his well-known brand of bearings.

Vandervell knew he couldn’t jump out of BRM and immediately launch into building his own car. He needed to first learn more about Grand Prix racing and its technologies. To that end, he bought a series of Ferraris, had them painted green, and campaigned them under the name “Thin Wall Special,” after his well-known brand of bearings.

The effort proved quite successful. Between 1949 and 1954, Vandervell’s burgeoning team won a number of races, at the hands of such drivers as Reg Parnell, Froilan Gonzalez and Peter Collins.

Vandervell would draw heavily on those first experiences when it came time to design his own car. His years thus far at the helm of a Grand Prix team had vindicated his already deep-rooted sense of pragmatism. It made sense that the chassis of the first design he and his staff would come up with was based extensively on the Ferraris with which they’d become so familiar.

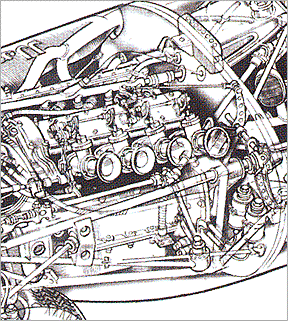

And since the basic car was more an extension of an existing design than an all-new development, it should be no surprise that Vandervell’s engine would come about in a similar ad-hoc fashion. That said, this new powerplant was a much more creative blending of parts and philosophies—with all the positive and negative attributes such a description implies.

And since the basic car was more an extension of an existing design than an all-new development, it should be no surprise that Vandervell’s engine would come about in a similar ad-hoc fashion. That said, this new powerplant was a much more creative blending of parts and philosophies—with all the positive and negative attributes such a description implies.

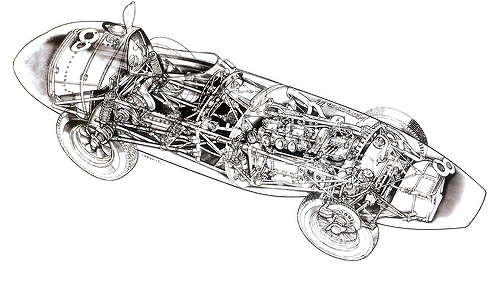

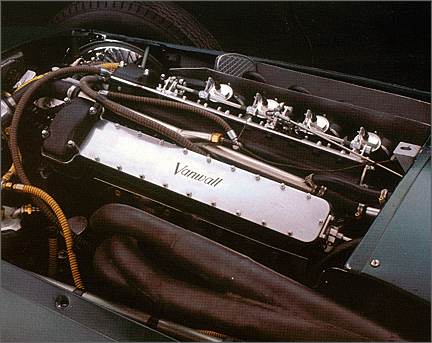

Vandervell reasoned that a suitable racing-engine design could be arrived at by starting with four Norton motorcycle cylinder and head assemblies, encasing them in one long water jacket, and mounting them to a common crankshaft and case. It wasn’t as nutty an idea as it may have first sounded. Motorcycle engines of the time produced far more power from a given displacement than car engines did. And Nortons, particularly the 500cc overhead-cam unit that Vandervell was looking at, were well established as the best.

With the matter of cylinders settled, Vandervell turned his attention to finding a suitable crankshaft and case. His son Anthony had apprenticed at Rolls Royce, working on the company’s B-Series military engines. He suggested they use a Rolls B40 crank and adapt that engine’s cast-iron case design to be made from aluminum.

And so, amid almost spy-novel secrecy imposed by Vandervell, he and his staff set about building their all-conquering crossbreed.

The choice of basing much of his car on proven, existing designs did indeed shorten the learning curve. But nothing could altogether eliminate that slope, which at times for Vandervell felt more like a cliff than a “slope” or “curve” or any other metaphorical summit that could be scaled without almost superhuman powers.

The choice of basing much of his car on proven, existing designs did indeed shorten the learning curve. But nothing could altogether eliminate that slope, which at times for Vandervell felt more like a cliff than a “slope” or “curve” or any other metaphorical summit that could be scaled without almost superhuman powers.

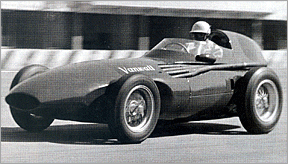

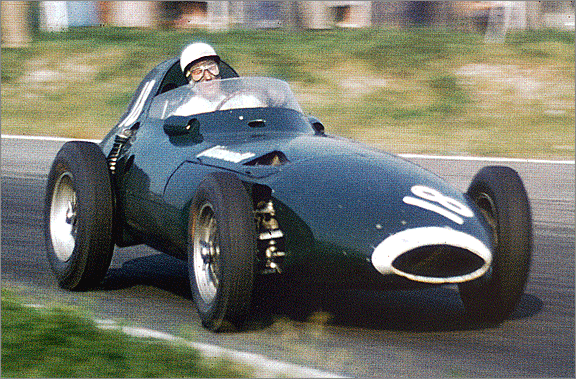

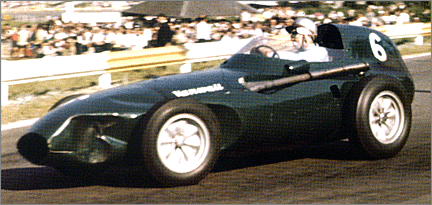

As could be expected, the first of the cars Vandervell and his design staff built didn’t look externally much different from the Ferraris that preceded them. But they now bore the moniker “Vanwall,” combining the Vandervell name with the bearing trademark.

Confirming Vandervell’s hypothesis of using the Norton cylinder components, the finished engine was potent enough to be competitive—235 horsepower on methanol fuel. But power would prove to be the least of the unit’s potential liabilities. During the ‘54 season, the engine was plagued by a succession of breakages that limited the cars to second-place finishes in a pair of small, non-championship events.

The following season, the team began fielding a second car, adding credence to the claim that the Vanwall effort was not some rich man’s tinkering, as some suspected, but rather a truly serious Grand Prix team. At several short, minor events that year, they won their first races.

Indeed, when the cars stayed running, they showed tremendous promise; the sight of Vandervell’s shiny green cars nipping at the Ferraris and Maseratis had ignited the passion of Britons wherever the Vanwalls raced. But the ‘55 season nonetheless proved frustrating as mechanical problems continued to sideline the cars.

Indeed, when the cars stayed running, they showed tremendous promise; the sight of Vandervell’s shiny green cars nipping at the Ferraris and Maseratis had ignited the passion of Britons wherever the Vanwalls raced. But the ‘55 season nonetheless proved frustrating as mechanical problems continued to sideline the cars.

What’s more, the still-ongoing mechanical gremlins weren’t the only issues they needed to address. Despite some tantalizingly strong runs so far, Vandervell and his staff began to note that the car’s handling wasn’t a match for its rivals. They were still a long way from the dream—winning a championship Grand Prix with an all-British car. And pursuing that goal would now require a complete remake of their original car.

Fortunately, two men who would eventually be considered among racing’s greatest designers were eager to do exactly that.

* * *

As with practically everything in racing, building a better Vanwall proved more difficult than imagined. Vandervell and his staff knew their car needed a whole new chassis design. Trouble was, what should they do to improve it over the original?

Overhearing them discussing the dilemma, Vanwall mechanic and transport driver Derek Wootton suggested they talk to a dear childhood friend of his who knew a thing or two about building cars.

Overhearing them discussing the dilemma, Vanwall mechanic and transport driver Derek Wootton suggested they talk to a dear childhood friend of his who knew a thing or two about building cars.

That friend turned out to be Colin Chapman.

As Chapman and Vandervell looked over the partially completed new frame, Chapman pointed out the design’s limitations bit by bit, flaw by flaw until finally it was deemed best to scrap the whole thing and start from scratch.

Vandervell didn’t so much as flinch at the suggestion, and Chapman was eager to begin; it would be his first Formula One project.

With the Vanwall set to get a completely new chassis, its body would have to be redesigned also. Frank Costin was just the man for the job. He was first and foremost an aircraft aerodynamicist, working for the de Havilland Aircraft Co. But he relished the freedom afforded by automotive projects, and by this time he had already worked with Chapman on several car designs.

With the Vanwall set to get a completely new chassis, its body would have to be redesigned also. Frank Costin was just the man for the job. He was first and foremost an aircraft aerodynamicist, working for the de Havilland Aircraft Co. But he relished the freedom afforded by automotive projects, and by this time he had already worked with Chapman on several car designs.

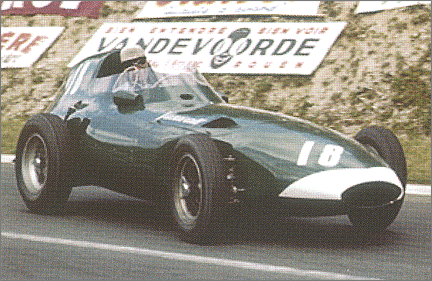

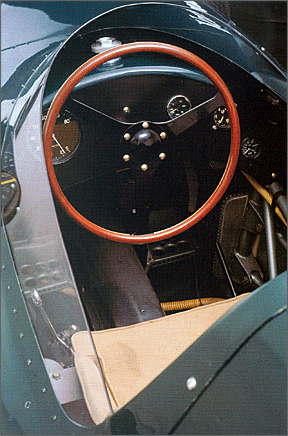

Chapman and Costin’s new Vanwall design was markedly different from its predecessor. It was powered by basically the same four-cylinder engine as before, but now, instead of being mounted to a parallel-rail, Ferrari-esque frame, the Vanwall engine was ensconced in a space-frame array of thin, round-section steel members carefully arranged to derive the most strength from the least weight.

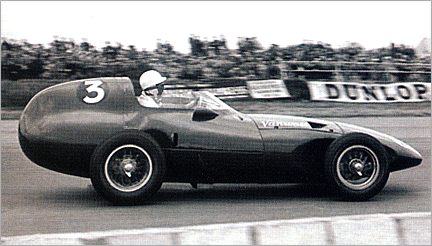

Even more obviously different was the body. Gone was the more conventional Ferrari-derived shape of the first Vanwalls. It had been replaced by a radical looking profile with a high, bulbous tail and a startling, pointy nose that extended unusually far beyond the front wheels. Although not unattractive, from some angles the car appeared to be almost a caricature of contemporary front-engine Grand Prix machines.

But unusual as it was, Costin’s design was effective. The new Vanwall proved quite fast, particularly on tracks that emphasized all-out speed. That fact wasn’t lost on Stirling Moss. He had signed with Maserati for the ‘56 season, but gained permission to race the new Vanwall when the Italian team didn’t need him.

But unusual as it was, Costin’s design was effective. The new Vanwall proved quite fast, particularly on tracks that emphasized all-out speed. That fact wasn’t lost on Stirling Moss. He had signed with Maserati for the ‘56 season, but gained permission to race the new Vanwall when the Italian team didn’t need him.

Britain’s day was almost here.

AINTREE. JULY 20, 1957.

THE BRITISH GRAND PRIX

It was round four of the Formula One World Championship and by this time, the hopes of Britons had been brought to a boil. Vanwall’s day of winning a championship Grand Prix surely had to be near. They’d come close so many times by now, and the team was looking stronger than ever. Perhaps it could happen here, at Britain’s greatest race. Anticipation hung heavy in the air around the thin, ornamented pillars and dark balustrades of the full-to-capacity grandstands.

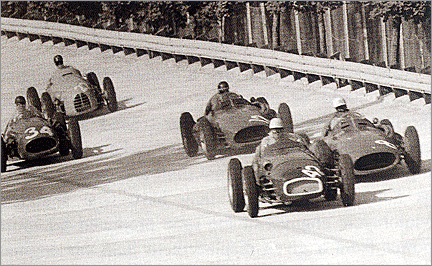

The cars burst into life. Engines were revved in anticipation, the high-strung, unmuffled powerplants collectively shouting a thick sonority that seemed almost solid enough to grab with your hands. Sitting on pole position was Moss, the unquestioned favorite of the fiercely loyal British crowd. Next to him was Jean Behra in a Maserati.

The cars burst into life. Engines were revved in anticipation, the high-strung, unmuffled powerplants collectively shouting a thick sonority that seemed almost solid enough to grab with your hands. Sitting on pole position was Moss, the unquestioned favorite of the fiercely loyal British crowd. Next to him was Jean Behra in a Maserati.

The starting flag fell and the pack of cars roared away, cutting and thrusting to gain position. Behra launched hard to snatch the lead from Moss at the start, but the Briton charged back, returning to the front by turn six. The crowed roared as he came across the line again, completing the first lap. Moss soon forced his lead to more than a second over Behra. After 20 laps, Moss had extended his lead to more than ten seconds.

Then it happened. It wasn’t obvious at first, just an occasional stammer of the engine as Moss accelerated along the grandstands. The crowd held its breath. Could this be the end? Already? Perhaps the misfiring was just an odd occurrence. Maybe it wouldn’t happen again.

Moss came back around. The slight stutter had become a pronounced misfire. As he headed for the pits, Behra flew past. Mechanics lifted the hood, tinkered a bit and closed it back up. Moss roared onto the track, rejoining the race in seventh place.

Moss came back around. The slight stutter had become a pronounced misfire. As he headed for the pits, Behra flew past. Mechanics lifted the hood, tinkered a bit and closed it back up. Moss roared onto the track, rejoining the race in seventh place.

The misfiring continued. Moss trundled back around, returned to the pits, and climbed out of the car. His race was over, it seemed.

But there was still one last hope. Teams were allowed to switch drivers during the race. Teammate Tony Brooks’ Vanwall was running strongly, but Brooks himself wasn’t. He was still recovering from a recent crash he’d had at Le Mans in an Aston Martin, and had already been passed by Vanwall’s junior driver for fifth place.

Brooks was signaled into the pits and helped out of the car. Moss leapt in, revved the motor and burst back onto the track, seemingly determined to either win the race or break the car trying.

Moss had given Vandervell and British racing fans a shot of hope the previous year when he opted to drive part-time for Vanwall. In doing so, he brought the team its biggest win yet, a non-championship race at Silverstone. Then, the spirit he had ignited in Britons turned to pure delight when he joined Vanwall full-time for ‘57.

Moss had given Vandervell and British racing fans a shot of hope the previous year when he opted to drive part-time for Vanwall. In doing so, he brought the team its biggest win yet, a non-championship race at Silverstone. Then, the spirit he had ignited in Britons turned to pure delight when he joined Vanwall full-time for ‘57.

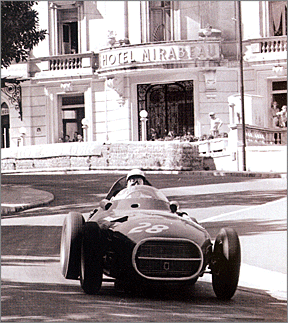

But despite finally having the undivided services of England’s top driver, the season had gone badly so far, with Moss crashing early at Monaco. The wreck was probably due more to faulty brakes than anything Moss did. Nonetheless, Vandervell was upset at him. Perhaps his new superstar wouldn’t work out as hoped. Vandervell’s doubts were further heightened when Moss then had to sit out the French Grand Prix and the Grand Prix at Reims due to sinus trouble caused by—of all things—a water skiing incident.

But today Moss looked unstoppable. He rejoined the race in ninth. By lap 30, he had already moved up to seventh. Then, on lap 34, he passed Juan Manuel Fangio for sixth.

Moss was moving swiftly through the pack, but the leader, Behra, was still 62.2 seconds ahead as they neared the race’s halfway point. Was it possible, even for someone of Moss’s caliber, to make up more than a minute in just 50 laps? Probably not. Those in the Vanwall pits were brittle and quiet from the tension.

On lap 40, Moss caught Luigi Musso for fifth and was now rounding the track at a risky, all-out pace that rivaled his qualifying time. Lap 46. He passed Peter Collins, taking fourth. The crowd was in a frenzy. Maybe Moss could catch the leader.

On lap 40, Moss caught Luigi Musso for fifth and was now rounding the track at a risky, all-out pace that rivaled his qualifying time. Lap 46. He passed Peter Collins, taking fourth. The crowd was in a frenzy. Maybe Moss could catch the leader.

But despite all the places Moss had gained in the last 20 laps, Behra was still 55 seconds ahead. Time was running out.

Just ahead of Moss, in third place, was Vanwall’s newest driver, Stuart Lewis-Evans. He had recently joined the team as a hasty replacement for Brooks as he recovered from his Le Mans crash, and for Moss as he recovered from his sinus problems.

When first informed of his top drivers’ maladies, the situation seemed bleak to Vandervell. There were few others available on such short notice. But team manager David Yorke had noticed the work of young up-and-comer Lewis-Evans as he began in Formula 3 races then quickly rose to Connaught’s Formula One team.

Vandervell took to Lewis-Evans immediately. Fast, yet calm behind the wheel, the young driver was good enough to hold his own with Brooks and Moss. And on a personal level, he liked the rookie’s modest and straightforward demeanor. Vandervell welcomed him enthusiastically as the team’s third driver for ‘57.

Vandervell took to Lewis-Evans immediately. Fast, yet calm behind the wheel, the young driver was good enough to hold his own with Brooks and Moss. And on a personal level, he liked the rookie’s modest and straightforward demeanor. Vandervell welcomed him enthusiastically as the team’s third driver for ‘57.

But despite Lewis-Evans’ strong showing today, Moss was still the team’s best hope to win the race. Ahead of Lewis-Evans, in second, was Mike Hawthorn. It would probably take the likes of Moss to beat him.

Moss began to drive even harder. His lap times fell to 2 minutes 2 seconds. But Behra’s team kept him apprised of Moss’s efforts. Behra responded by lapping at 2 minutes .004 seconds, a new record. Although nearly halfway across the track from each other, the two were battling relentlessly. On lap 53, Moss rounded the circuit at an astonishing 1 minute 59.2 seconds, the first lap at Aintree over 90 mph.

Could the car take such punishment? The Vanwalls still had yet to completely shake their reliability problems and Moss was pushing harder than the cars had ever been driven.

Moss continued to gain ground, but with 22 laps left he was still behind by 28 seconds. His valiant effort had moved victory out of the realm of the impossible, but it was still unlikely. On lap 69 he passed Lewis-Evans for third leaving just Hawthorn before he could attack Behra.

Moss continued to gain ground, but with 22 laps left he was still behind by 28 seconds. His valiant effort had moved victory out of the realm of the impossible, but it was still unlikely. On lap 69 he passed Lewis-Evans for third leaving just Hawthorn before he could attack Behra.

Then all hell broke loose. The clutch on Behra’s Maserati burst into pieces, rupturing its housing and spreading shrapnel across the track. Effectively powerless, the bright red car slowed to a stop. Then Hawthorn’s Ferrari roared through the debris field left by Behra’s car and punctured a tire.

The crowd and commentators leaped into a frenzy. Moss was in the lead and Lewis-Evans was in second—a one-two British sweep at their home race.

But then rose the specter of the Vanwall’s reliability problems, reminding everyone that the race had yet to be won. Just two laps after Moss took the lead, Lewis-Evans dropped out with a broken throttle.

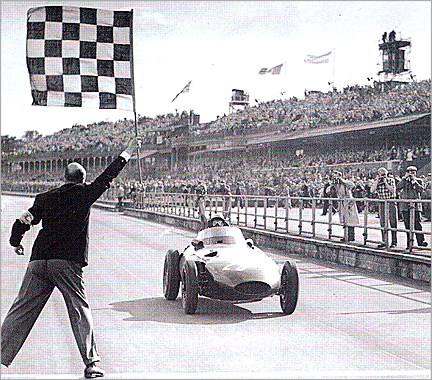

The exhilarating one-two was no more, but Moss was still running strong and staying in front. After a cautiously executed fuel stop, he remained in the lead, 41 seconds ahead of Musso. Completing the race at a careful, parts-friendly pace, Moss was the first to the checkered flag, thrusting his right arm into the air triumphantly as he crossed the line.

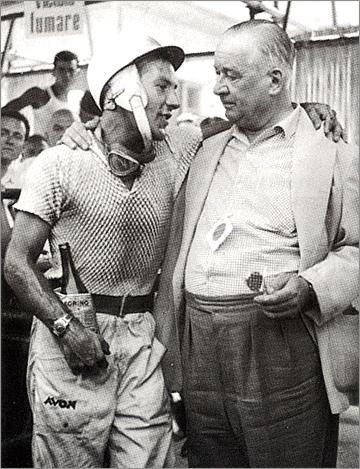

Before all of the cars had even passed the grandstand, the wildly excited crowd rushed onto the field, forcing some drivers to dodge and weave to avoid hitting anyone. In the winner’s circle, black-faced Moss and Brooks stood before the throng, flanking Tony Vandervell as he raised the silver cup over his head and flashed a rare smile for photographers.

Before all of the cars had even passed the grandstand, the wildly excited crowd rushed onto the field, forcing some drivers to dodge and weave to avoid hitting anyone. In the winner’s circle, black-faced Moss and Brooks stood before the throng, flanking Tony Vandervell as he raised the silver cup over his head and flashed a rare smile for photographers.

Winning Britain’s most prestigious race in a British car was certainly a tremendous accomplishment, but it couldn’t completely silence all the doubts. Perhaps it was a fluke? What’s more, the victory had come only with some generous helpings of plain, dumb luck. This isn’t said to take anything away from Moss’s effort. His performance that day was nothing short of epic, and only such a torrid drive could have put him in position to benefit from Behra’s and Hawthorn’s misfortune.

Finally, England’s three-decade Grand Prix drought was over. But still, it would take more than just a single victory—albeit a big one—to completely seal Vanwall’s position as the British equal of teams from the Continent. And the following race, the German Grand Prix, gave remaining skeptics further cause to doubt; Moss and Brooks finished fifth and ninth, respectively.

This, however, would prove to be only a minor stumble in what was about to become a Vanwall breakout. The team next went to Pescara—Ferrari and Maserati territory. Despite Vanwall’s rivals having the home-track advantage, Moss grabbed the lead in the second lap and never let it go, beating Fangio by over three minutes.

This, however, would prove to be only a minor stumble in what was about to become a Vanwall breakout. The team next went to Pescara—Ferrari and Maserati territory. Despite Vanwall’s rivals having the home-track advantage, Moss grabbed the lead in the second lap and never let it go, beating Fangio by over three minutes.

Again came that rare, unrestrained grin to Vandervell’s face.

The following race was the Italian Grand Prix at Monza. This was an even more important trophy to the Italians, every bit the point of national pride to Ferrari and Maserati that Aintree had been to Britons. The race was on Vandervell’s 59th birthday, and no better present could have been offered: Despite fierce opposition from the Italian teams, Moss routed the entire field. Fangio’s Maserati was the only car to finish on the same lap, and the nearest Ferrari was two laps down.

It was the first time a British car had ever won the Italian Grand Prix. There could now be no doubt.

Britain had arrived.

* * *

Vandervell surely felt vindicated, his years of day-and-night effort having accomplished what no other Briton had ever been able to. There was, however, one remaining prize to be won: the championship. And so, like a mountain climber on the last precipice before the summit, Vandervell steeled his team for the final assault.

But the pursuit of this highest honor would culminate in a tragedy for which Vandervell would find himself wholly unprepared. It would change him forever.

For 1958, Vanwall would enter only the Grands Prix that counted toward the championship. By the season’s final event, the Moroccan Grand Prix, the team had won five times, with Moss earning enough points to be solidly in contention to win the Drivers’ World Championship. What’s more, Vanwall was poised to have a good chance at claiming the inaugural Constructors’ Cup.

For 1958, Vanwall would enter only the Grands Prix that counted toward the championship. By the season’s final event, the Moroccan Grand Prix, the team had won five times, with Moss earning enough points to be solidly in contention to win the Drivers’ World Championship. What’s more, Vanwall was poised to have a good chance at claiming the inaugural Constructors’ Cup.

Moss lead the entire race, setting a lap record along the way. It was the team’s fourth victory in a row, sixth of the season. This wouldn’t, however, be enough to deliver Moss a well-deserved championship. Ferrari driver Mike Hawthorn finished immediately behind Moss that day, high enough to snatch the trophy from him by one point. Nonetheless, the race’s results were good enough to give Vanwall the Constructors’ Cup, thus firmly spearing the Union Jack into the icy summit of the world auto-racing mountain.

There was much to rejoice over. They had finally reached the top, trouncing the Italians in a second consecutive season and winning more races than any other team in ‘58. But across the dry, sandy Ain-Diab circuit an ominous cloud of oily black smoke had earlier reared, blotting out the celebration. The engine in Stuart Lewis-Evans’ car had locked up on lap 12, causing him to slide off the track. His fuel tank burst and the car ignited into a fireball. In a nearby hospital he lay, horribly burned. Barely alive.

There was much to rejoice over. They had finally reached the top, trouncing the Italians in a second consecutive season and winning more races than any other team in ‘58. But across the dry, sandy Ain-Diab circuit an ominous cloud of oily black smoke had earlier reared, blotting out the celebration. The engine in Stuart Lewis-Evans’ car had locked up on lap 12, causing him to slide off the track. His fuel tank burst and the car ignited into a fireball. In a nearby hospital he lay, horribly burned. Barely alive.

Until this time, Tony Vandervell had been relatively lucky in terms of on-track incidents. Yes, there had been crashes over the years, but none of his drivers had been badly injured. Vandervell was left ashen, hollow from the day’s tragedy. Feeling personally responsible for the crash, he said it was his “bloody stupid hobby” that had put Lewis-Evans on a stretcher.

On the flight home, Vandervell asked friend Lofty England of Jaguar to take over the Vanwall team. England politely declined, at the same time trying to ease Vandervell’s sense of hopelessness and loss. He reminded Vandervell that this was simply the nature of their sport, while gently encouraging him to continue his worthwhile cause while still on top. But it was to no avail. Vandervell was devastated.

Despite receiving the best treatment available at one of Britain’s finest hospital burn units, Lewis-Evans died of his injuries six days after the race.

Despite receiving the best treatment available at one of Britain’s finest hospital burn units, Lewis-Evans died of his injuries six days after the race.

And just as life slowly resigned its hold on the young driver and wisped aimlessly into the East Grinstead sky, so did the desire to pursue auto racing gather up and leave Tony Vandervell.

The brief, brilliant Vanwall era was over.

EPILOGUE

Over the months immediately following Lewis-Evans’ death, Vandervell’s health began to decline. In January 1959, he officially disbanded the team. Despite the finality of that announcement, there were several half-hearted attempts to continue, including the creation of a mid-engine car that appeared at Silverstone in 1961.

But Tony Vandervell’s fiery determination and unwavering vision were gone. Without it, there was little or no hope for the team, even though much of the same hard-working, talented staff remained. Vandervell died in 1967, at the age of 68.

But Tony Vandervell’s fiery determination and unwavering vision were gone. Without it, there was little or no hope for the team, even though much of the same hard-working, talented staff remained. Vandervell died in 1967, at the age of 68.

The success of the 1956-58 Vanwall design dramatically helped the careers of Colin Chapman and Frank Costin; Chapman’s Lotus Cars would field a staggering array of successful Formula One cars, and Costin went on to design a number of significant racing-car bodies.

Stirling Moss was forced to retire from driving in 1962, following a crash at Goodwood that left him almost entirely unconscious for 38 days and partially paralyzed for months after that. His second-place, one-point deficit to Mike Hawthorn in 1958 would be the closest he would ever come to winning the sport’s top honor.

During this time, the gradual trend toward mid-engine designs in Formula One had accelerated; Vanwall’s 1958 Constructors Cup was the last time a front-engine car would ever win the title. Thus, the zenith of Vanwall was, in a larger sense, the last bright act for the configuration that had ruled Grand Prix since its beginning, more than a half-century earlier.

During this time, the gradual trend toward mid-engine designs in Formula One had accelerated; Vanwall’s 1958 Constructors Cup was the last time a front-engine car would ever win the title. Thus, the zenith of Vanwall was, in a larger sense, the last bright act for the configuration that had ruled Grand Prix since its beginning, more than a half-century earlier.

Following Vanwall’s two seasons on top, other British manufacturers took up where Vandervell and his crew left off. The BRM effort from where he had started his odyssey finally reached its stride and began to amass victories. At the same time, other British teams began marking their own successes on the international scene.

From then on, Britain would remain a formidable power in Formula One racing, a legacy for which Tony Vandervell would surely be proud.