Luigi “Gigi” Villoresi was one of the world’s best drivers in the late 1940s, so it’s no surprise Enzo Ferrari asked him to join the fledgling Scuderia Ferrari in 1949. Villoresi accepted, and over the next four years he scored numerous victories for the small company.

Luigi “Gigi” Villoresi was one of the world’s best drivers in the late 1940s, so it’s no surprise Enzo Ferrari asked him to join the fledgling Scuderia Ferrari in 1949. Villoresi accepted, and over the next four years he scored numerous victories for the small company.

The partnership produced impressive results, but Villoresi personally despised Enzo Ferrari. Ferarri, Villoresi insisted, was responsible for the death of his beloved brother a decade earlier.

Emilio Villoresi had been an Alfa Romeo factory driver before World War Two, when Alfa’s racing team was run by Enzo Ferrari. On a warm June afternoon in 1939, Ferrari arranged an elaborate luncheon at the Monza circuit to show of the company’s new 158 Alfetta. It was Emilio’s job to demonstrate the car’s abilities at speed.

It should have been a pleasant, uneventful afternoon, but tragedy struck. Emilio did two laps without problems. Then, on the third, he swerved off the track, crashed into a tree and was killed.

For Gigi, having his brother die pointlessly was terrible enough. But Ferrari inflamed Villoresi’s raw emotions by treating the incident with shocking disdain.

“I asked Enzo if I could see the remains of the car, but he refused,” Villoresi told Motor Sport magazine in March, 1997. “And when I asked him what had happened, he told me he thought my brother had eaten too much at lunch and perhaps had indigestion, which had caused him to go off the road.… So I really did not like [Enzo Ferrari].”

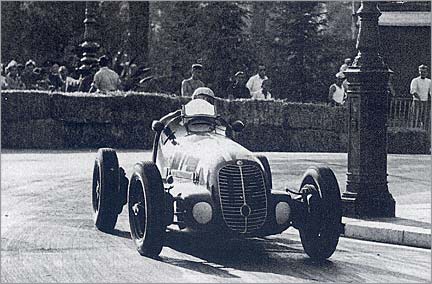

Gigi Villoresi was born into a well-to-do Milanese family in 1909. He and Emilio (who was generally considered the better driver) began racing in 1931 with a Fiat Balilla Sport. Gigi wasn’t an instant star. Instead, he steadily rose through the ranks, as evidenced by a fifth in class at the 1933 Mille Miglia and a third-place finish in the 1935 Coppa Ciano voiturette race at Montenero.

In 1937, Villoresi scored his first major win, piloting a Maserati 6CM to victory at Masaryk in Czechoslovakia, and his career began to take off. He won the Italian 1,500cc sports car championship that year, then became a Maserati test driver in 1938. In 1939, he won his second Italian 1,500cc title.

Given his success with the marque, it’s little wonder Villoresi claimed his first automotive love was for Maserati. “The three [Maserati] brothers were really wonderful people,” he told Sports Car International in 1991. “They were easy to get along with. In a way, you felt obliged to do your best, but you didn’t get a talking to if your results weren’t as good as expected. I immediately felt at home with them, and that feeling also increased my will to drive well. I expressed myself best as a driver with a Maserati car.”

By 1940, Europe had plunged into war. Motor racing was halted shortly afterward, and Villoresi spent part of the conflict as a prisoner of war. When hostilities finally ended, he was released, his black hair turned white from the stress of his internment.

By 1940, Europe had plunged into war. Motor racing was halted shortly afterward, and Villoresi spent part of the conflict as a prisoner of war. When hostilities finally ended, he was released, his black hair turned white from the stress of his internment.

Villoresi dove back into racing with aplomb, driving a works Maserati 4CL to wins in the 1946 Nice Grand Prix—likely the first postwar European race—and at Voghera. He also won the Targa Florio, and finished seventh in the Indy 500 despite a lengthy stop for repairs.

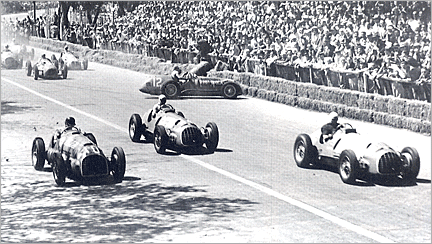

The next two years were Villoresi’s most successful. He won the Italian driver’s championship in 1947 and 1948 with a supercharged 1,500cc Maserati Grand Prix car. With Italy the center of postwar racing, Villoresi was essentially World Champion before there was such a title.

At the same time, Enzo Ferrari, who had left Alfa Romeo before the war, was beginning to construct his own racing cars—12-cylinder Grand Prix machines that showed considerable potential from their first outing. But no matter how good Ferrari’s cars were, he needed top-notch driving talent to become a true power in motor racing.

So, despite their shared dislike for one another, Ferrari decided to ask Villoresi to join his team.

Ferrari’s first gesture came while Villoresi was racing a Maserati in England in early 1949. Enzo sent word that, if Villoresi was interested, there would be a Ferrari single-seater for him to race in the Brussels Grand Prix, as well as a sports car to drive in Luxembourg.

Intrigued by the offer, Villoresi went to Ferrari’s house to discuss it. With Enzo lying sick in bed, the two men acknowledged their mutual dislike but eventually agreed to put it aside for their common benefit. Villoresi left with a signed contract.

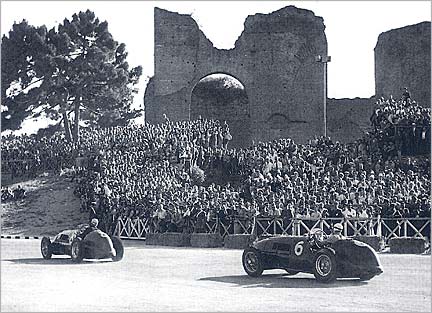

Villoresi and the prancing horse proved to be a good match from the beginning. In 1949, his first season with the team, the 40-year-old driver won the Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort, F2 races at Rome, Lake Garda and Brussels, and a sports car race at Luxembourg. He finished second in the Swiss and Belgian Grands Prix, and placed third in the Daily Express Trophy at Silverstone.

Villoresi and the prancing horse proved to be a good match from the beginning. In 1949, his first season with the team, the 40-year-old driver won the Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort, F2 races at Rome, Lake Garda and Brussels, and a sports car race at Luxembourg. He finished second in the Swiss and Belgian Grands Prix, and placed third in the Daily Express Trophy at Silverstone.

Gigi’s success continued in 1950. He won the F2 races at Marseilles, Erien and Monza, as well as Formula Libre events at Rosario and Buenos Aires. He finished second in the non-championship Grands Prix of Pau, San Remo and Zandvoort, F2 races at Rome and Mons, and a sports car race in Luxembourg.

But Villoresi’s luck turned for the worse later that year at Geneva. “I was down the field and someone up front blew his engine and spread oil over the road,” he explained in the Motor Sport interview. “I spun, hit the straw bales and overturned. Luckily, I was thrown out of the car, but was lying in the middle of the road. You know, in all my racing, I broke 24 bones in my body. Most of them were in that crash at Geneva.”

Broken bones weren’t the only injuries Villoresi suffered in the crash: He was in a coma for three days and lost the top of one of his fingers. He later admitted he was lucky to have survived, though three spectators were not so fortunate.

Villoresi didn’t race for the rest of 1950, and many said he would never drive again. And even if he did, would Ferrari still want him? Villoresi wasn’t the team’s only star driver. His friend and protégé Alberto Ascari showed every sign of eclipsing his mentor.

* * *

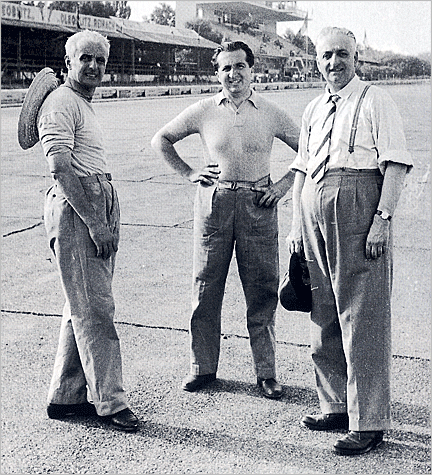

Ascari and Villoresi had met before the war, when Alberto, the son of renowned racer Antonio Ascari, was competing on motorcycles. Gigi and Alberto soon formed a business partnership outside of racing, and Villoresi introduced Ascari to Mietta Tivola, the woman Alberto would later marry.

When the war ended, Ascari was 27. He seemed ready to settle down and focus solely on their mutual business pursuits, but he quickly jumped into the driver’s seat after watching one of Villoresi’s postwar races.

At first, Ascari was content to learn from his older friend, and Villoresi was happy to teach him. In 1947, Ascari’s first season driving alongside Villoresi, the student showed promise but was no great threat to his teacher. The best finish Ascari could manage that year was a fourth place at Nice.

The following year, however, Ascari’s latent talent began to blossom under Villoresi’s tutelage. At San Remo, Ascari drove a brand-new Maserati 4CLT/48 to victory over Villoresi in a similar car, a scenario that would be repeated with increasing frequency over the next several years.

The following year, however, Ascari’s latent talent began to blossom under Villoresi’s tutelage. At San Remo, Ascari drove a brand-new Maserati 4CLT/48 to victory over Villoresi in a similar car, a scenario that would be repeated with increasing frequency over the next several years.

In 1949, Ascari joined Ferrari with his mentor. “We were great friends,” Villoresi said of Ascari. “He was tomorrow’s driver, and I was today’s.”

By 1950, Ascari had won several Grands Prix. Villoresi, realizing tomorrow was at hand, stepped down from the number-one position in favor of his friend—a decision that reveals much about Gigi as a person.

By all accounts, Villoresi was both a gentleman and a gentle man. In the Fall 1951 issue of Autocourse, Count Giovanni Lurani, who raced with and against Villoresi both before and after WWII, described him as “a most sensitive human being, but [with a] boyish sense of fun which adds lightness to sport.”

As an example, Lurani wrote, “at Crystal Palace in ‘37, he overtook me in an acrobatic fashion, and I was dismayed at the finish. But Gigi’s open smile was enough to dissolve my temper very quickly.”

Villoresi’s gentle nature was evident outside of the race car. Once, when Lurani and Villoresi were travelling together by car, Gigi suddenly pulled over. “[He] wanted to listen to a thundering cascade in the silence on top of the mountains,” wrote Lurani. “We [soon] sped off and stopped again for two hours on top of the Simplon to collect flowers. Then we lay in the sun and enjoyed the stillness, only broken by far-away cowbells, then off again at full speed to Milan to make up for lost time.”

Racing was just as much a part of Villoresi’s character, however, and despite the rise of Ascari, Gigi wasn’t through yet. He spent six months recovering from his accident at Geneva, then started the 1951 season with wins at the Syracusa GP and the Coppa Intereuropa at Monza. He then scored one of the greatest victories of his life.

* * *

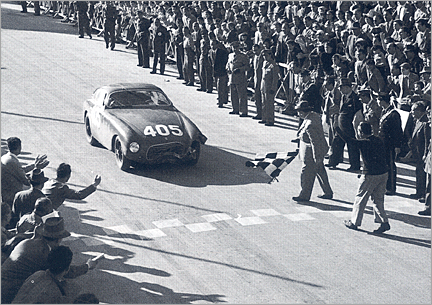

The Mille Miglia was like no other race. It ran a full 1,000 miles across twisty mountain roads and through towns filled with spectators just inches off the tarmac. Due to the difficulty and danger, a win at the Mille Miglia ensured a driver’s name would be etched in the record books. “It was a wonderful adventure,” Villoresi said in Ferrari 1947-1997. “In those days, all drivers had one goal: to win the Mille Miglia, because it gave you an extra something.”

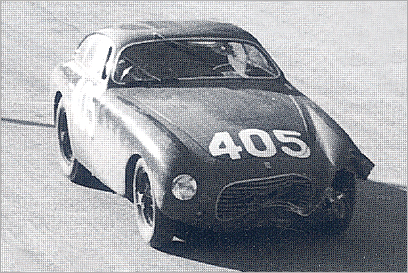

Ferrari entered 11 works cars for the ‘51 Mille, including three 340 Americas. The fast 340s were widely expected to take the overall win: Their 4.1-liter V12s made an impressive-for-the-day 240 hp and plenty of torque. “Ferrari made really good engines, [though] the chassis were never up to the job,” Villoresi remarked many years later. “Driving a Ferrari of the period was anything but easy.”

Furthermore, Villoresi did not want the barchetta that was offered to him. “I wanted a closed car… and in addition I insisted that my car’s exhausts [be] fitted with silencers, because I did not want to sit there for 13 consecutive hours in a bordello of noise.”

After much protest, Ferrari gave Villoresi his coupe. Anticipating a wet race, the driver had a third wiper mounted above the windshield to augment the two below.

Villoresi’s prediction was correct: The race was drenched from the start, making the already treacherous circuit that much more brutal. Ascari crashed his 340 early on, just outside of Brescia. Then, to everyone’s surprise, Giannino Marzotto blasted past Villoresi to take the lead, driving a less-powerful 2.6-liter Ferrari.

Villoresi’s prediction was correct: The race was drenched from the start, making the already treacherous circuit that much more brutal. Ascari crashed his 340 early on, just outside of Brescia. Then, to everyone’s surprise, Giannino Marzotto blasted past Villoresi to take the lead, driving a less-powerful 2.6-liter Ferrari.

The rain continued to pour down as the cars snaked through the rugged terrain. Villoresi chased Marzotto, gradually chipping away at his five-minute lead. As Villoresi fought to keep his wild, powerful car on the road, he knew he was on the verge of crashing. But his co-driver, Pasquale Cassani, urged him on. “I had the steering wheel, I had the brakes, for what they were worth, but Cassani had the enthusiasm,” Villoresi recalled in Ferrari 1947-1997.

Villoresi’s sense that they were going to wreck proved all too accurate: They soon went off the road at a dangerous bend, hitting a motionless car that had already crashed there. But they quickly got the Ferrari back onto the road and pressed on, despite steering that was no longer quite right.

The third windshield wiper proved to be more of a detriment than a help; water poured into the cabin through the hole in the bodywork. “[But] the worst problem was peeing,” remembered Villoresi. “We had to go and there was little we could do about it.”

Villoresi finally caught up to Marzotto, who had been forced to retire with axle trouble, and took the race lead. But then the 340’s transmission began to lose gears. Soon, Villoresi only had fourth, and Giovanni Bracco’s Lancia was just ten minutes behind and closing. By the time they reached Florence, Bracco had narrowed the gap to just 2.5 minutes.

Then, miraculously, the sun came out. Villoresi was finally able to use all his car’s power, and quickly pulled free of Bracco’s relentless charge. The Ferrari burst into Brescia around 5:00 p.m., victorious by a convincing 20 minutes. Villoresi had fixed his place among the winners of the sport’s most demanding event.

It was the fourth time in as many attempts Ferrari had won the Mille Miglia, and a jaded Enzo didn’t congratulate his driver. But the crowd in Brescia gave Villoresi the hero’s welcome that befits any Mille Miglia winner, and he basked in the attention. “Applause, shouting and compliments, but the thing that touched me most was a hug from my mother, whom I had imagined to be in Milan,” he remembered.

Villoresi backed up his Mille Miglia victory with F1 wins at Syracusa and Pau, F2 victories at Genoa and Marseilles, and sports car wins at Senigalia and the Coppa Intereuropa, plus a second-place finish in La Carrera Panamericana.

Villoresi backed up his Mille Miglia victory with F1 wins at Syracusa and Pau, F2 victories at Genoa and Marseilles, and sports car wins at Senigalia and the Coppa Intereuropa, plus a second-place finish in La Carrera Panamericana.

Over the next two years, he remained a threat behind the wheel of a Ferrari. In Formula One, he was a regular second- or third-place finisher behind teammate Ascari and Juan Manuel Fangio; in sports cars, he won the 1953 Tour of Sicily and a race at Monza. By this time, however, he was getting well into his 40s, and wins in major events became scarcer every year.

For the 1954 season, Villoresi and Ascari left Ferrari to join Lancia. Ascari had repaid his mentor’s kindness by securing the Lancia contract, with its much larger paycheck and the promise of better machinery. Lancia did not debut its D50 Grand Prix car until the final race of the year, so in the meantime Villoresi was loaned to Maserati and Ferrari. He finished sixth at Monza and fifth at Reims.

Villoresi returned to Lancia for the start of the 1955 season. He won the Sestrieres rally with Ascari and came in fifth at the Monaco Grand Prix, the marque’s highest-ever F1 finish. Shortly after the Monaco race, Ascari was killed while testing a Ferrari sports car at Monza.

Gigi was stunned by the loss of his dear friend, but he continued to race. In 1956, he raced OSCAs in a number of events, taking third place in the Tour of Sicily, and drove in five F1 races with a Maserati 250F, finishing fifth in Belgium and sixth in Britain. His last Fl race was at Monza, where his car expired just as he was overtaking Fangio.

Later that year, Villoresi was hospitalized after a severe crash at Rome in a Maserati sports car. He announced his retirement in early 1957. But racing was still in his blood, and he participated in a few rallies over the next couple of years.

Later that year, Villoresi was hospitalized after a severe crash at Rome in a Maserati sports car. He announced his retirement in early 1957. But racing was still in his blood, and he participated in a few rallies over the next couple of years.

In the decades that followed, Villoresi often appeared at races, a proud, noble link to Grand Prix racing’s heroic past. He died of natural causes in 1997 at the age of 88.

Despite all their shared success, Luigi Villoresi and Enzo Ferrari never became friends, but each made small overtures. According to Villoresi, “[Some time after I retired] in a large gathering of former drivers, in front of everyone, Ferrari said, ‘Look, this is Villoresi, the only driver I have never been on first-name terms with.’ He gave me a hug, and from then on he called me ‘Gigetto.’”